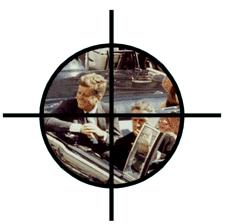

And here is an advertisement that appeared in the Dallas Morning News on the day of the assassination, November 22nd, 1963. It too reflects rightist disagreement with Kennedy's policies.

Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith was a liberal (actually, socialist) member of the Kennedy administration. On the afternoon of the assassination, before he knew that Oswald had been arrested, he told Arthur Schlesinger:

We let the Right inject this poison in the American bloodstream — and this is the result. (William Manchester, Death of a President, p. 354)Penn Jones was an upright citizen of Midlothian, Texas and a pioneer conspiracy buff. He outlined the sort of people he believed killed Kennedy:

We are convinced some of the instigators of the assassination were people of the lowest sort. On their own merits, none of them would gain an invitation to your home. For the most part they were bribe takers, punks, pimps, homosexuals, perverts, and cheap gamblers. They have now gained a large amount of respectability. And until they are brought to justice, will grow more dangerous. (Author's introduction, Forgive My Grief Vol 1, 2nd printing, 1966)Right wing ex-congressman Martin Dies explained, in the journal of the John Birch society, his belief that a Communist conspiracy killed Kennedy:

Knowing Oswald's Communist beliefs; his two and one-half years of residence in the Soviet Union enjoying special privileges, and where he married a Russian girl; his renunciation of American Citizenship and loyalty; his affirmation of allegiance to Russia; and, his televised statements and activities in favor of Castro, it is inconceivable that the Warren Commission could reach the absurd conclusion that Oswald acted alone and that Jack Rubenstein acted alone. It may be answered that I do not have one hundred percent proof that this assassination was probably the act of the International Communist Conspiracy. I submit that time and time again the Commission prefaced its findings with the word "probably." In my opinion, anyone who studies this Report and the testimony of the witnesses, and who understands and recognizes the nature and modus operandi of the International Communist Conspiracy, will agree that it is far more probable that the assassination was the act of the Communist Conspiracy and not solely the act of Oswald — and that Oswald was liquidated to prevent him from talking. (American Opinion, October, 1965, p. 32)The Birch society issued a preformatted newspaper ad to each of its chapters that they could — if the could afford it — place in local newspapers. They also issued members stickers designed to be affixed to outgoing letters. Thanks to Prof. Steve Hauser for providing both of these items, and were reprinted in The White Book of The John Birch Society for 1963.

Kenneth A. Rahn, of the University of Rhode Island, has compiled a fine collection of sources showing the reaction of various political factions to the assassination.

In the latest effort to recycle the Camelot myths, Frank Rich has published a delusional article in New York Magazine under the title, "What Killed JFK: The Hate That Ended His Presidency is Eerily Familiar" in which he draws a straight line from Kennedy's assassination to imagined threats against President Obama arising from conservatives and the tea party movement.One of the great ironies of modern American politics, of course, is that those who are quickest to see "hate" on the other side of the political spectrum are in fact those most consumed by it.His tortured logic runs like this: President Kennedy was a victim of hatred coming from the far right; President Obama ran for election in 2008 as a reincarnation of JFK, supported by surviving members of the Kennedy family; his mission was to restore the ideals of Camelot, and thus to reinvigorate liberalism; now he is the target of the same vitriol from the right that brought down Kennedy. Therefore, the tea party movement, the far right, and conservatives in general are dangers to the public welfare. It is probably useless to point out to Mr. Rich that none of the things he believes about Kennedy or the Kennedy assassination is remotely true so that none of them has anything to do with the politics of the present time.

Those who desperately want to believe that President Kennedy was the victim of a conspiracy have my sympathy. I share their yearning. To employ what may seem an odd metaphor, there is an esthetic principle here. If you put six million dead Jews on one side of a scale and on the other side put the Nazi regime — the greatest gang of criminals ever to seize control of a modern state — you have a rough balance: greatest crime, greatest criminals.Along similar lines, Michael Beschloss discusses the process of rationalization:But if you put the murdered President of the United States on one side of a scale and that wretched waif Oswald on the other side, it doesn't balance. You want to add something weightier to Oswald. It would invest the President's death with meaning, endowing him with martyrdom. He would have died for something.

A conspiracy would, of course, do the job nicely. Unfortunately, there is no evidence whatever that there was one. (New York Times, February 5, 1992)

Many Americans are now certain that had JFK lived to win a second term, he would have spared the nation its tragic adventure in Southeast Asia. The assassination in Dallas obliterated the rationality and hope that were the outward hallmarks of the Kennedy presidency and of most of American public life. That sense of confident well-being was replaced with what the novelist Don DeLillo described as "a world of randomness." Many presume that without the disillusionment that followed Dallas and Vietnam, we would be living in a happier and more innocent country. And because it is difficult to tolerate the notion that this historical transformation could turn on something so trivial as the caprice of a surly little egotist, a grander design has been sought — in the Mafia, in foreign intelligence services, in the Cubans, the Russians, the CIA. (Newsweek, November 22, 1993, p. 62.)And finally, Jackie Kennedy's comment to her mother on hearing that a leftist had been arrested for killing her husband:

He didn't even have the satisfaction of being killed for civil rights . . . . It's — it had to be some silly little Communist. (Manchester, Death of a President, p. 407)